In every handful of soil, an invisible process is constantly at work. One that drives plant nutrition, builds soil structure, and regulates the global carbon cycle. This process is microbial decomposition: the breakdown of organic matter by soil microorganisms. Though largely hidden from view, it is fundamental to how ecosystems function and how agriculture sustains itself.

Understanding how decomposition works, what influences its rate, and how it contributes to long-term soil health is essential for anyone seeking to manage land more effectively and sustainably.

What Is Decomposition?

Decomposition is the biological breakdown of complex organic compounds into simpler, more bioavailable molecules.

The organic matter in soil comes from various sources:

- Aboveground inputs such as senescent leaves, stems, and animal remains

- Belowground contributions including root exudates, decaying roots, and soil fauna

- Agricultural amendments such as compost, manure, and crop residues

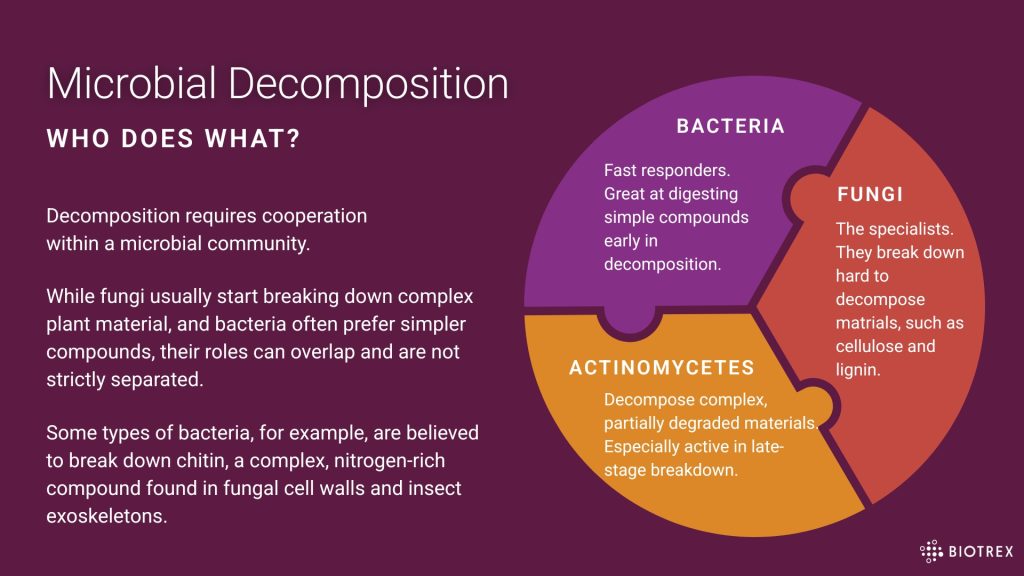

In soils, decomposition is almost entirely mediated by microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and actinomycetes. Microorganisms interact with diverse organic inputs by producing specialised enzymes tailored to the chemical composition of each material. Soil microbes can decompose both readily available substrates and more complex compounds. This initiates the release of nutrients and the transformation of organic matter across all input types.

Bacteria are metabolically diverse and often dominate in the early stages of decomposition, particularly when easily degradable substrates, such as carbohydrates and peptides, are abundant.

Fungi are the primary decomposers of more recalcitrant plant organic materials, including cellulose and lignin.

Actinomycetes, a group of filamentous bacteria, play a key role in the decomposition of complex and partially degraded organic compounds. They are particularly active in the later stages of decomposition.

Decomposition is a complex metabolic process that often requires interdependence within the soil microbial community. Although fungi typically initiate the breakdown of complex plant residues, the roles of microbes are not strictly defined. For instance, certain bacterial taxa are thought to be responsible for the degradation of chitin, which is a structurally complex, nitrogen-rich polymer found in the cell walls of fungi and the exoskeletons of insects (Beier and Bertilsson, 2013).

The Three Stages of Microbial Decomposition

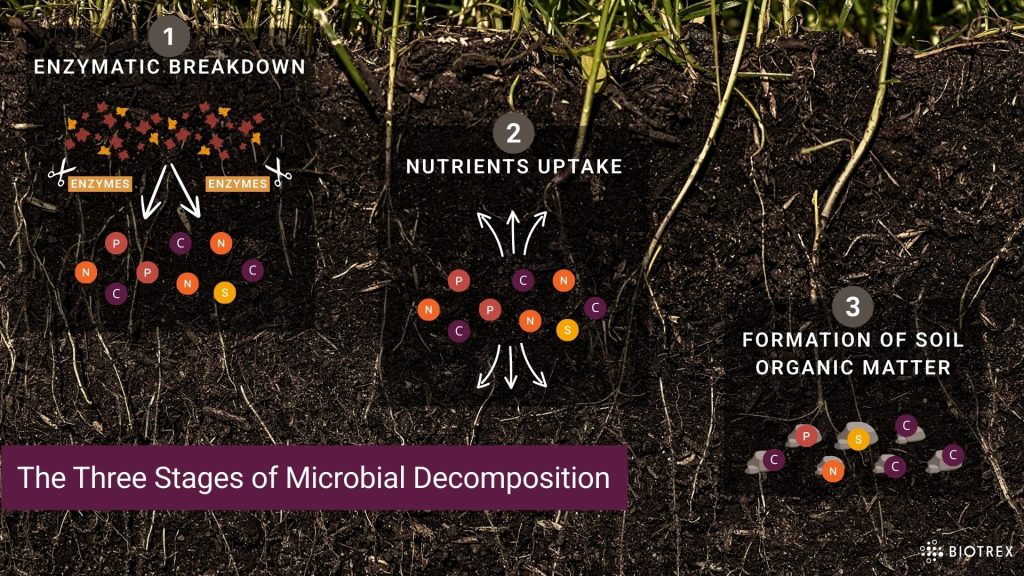

1. Enzymatic breakdown of organic matter

At the beginning of decomposition, soil is full of organic materials like dead leaves, roots, and stems. But for microbes, these materials aren’t ready-to-eat meals. The compounds in plant residues are made up of large, complex molecules, far too big to pass through the microbial cell wall. To access the nutrients and energy locked inside, microbes must first break these molecules down.

This is why they produce and release extracellular enzymes – special tools that work outside their cells, in the surrounding soil. These enzymes act like scissors or molecular knives, cutting large polymers into smaller, manageable pieces that microbes can then absorb and use. These enzymes are what make decomposition happen.

Different enzymes target different components of organic matter. One of the most common is cellulase, which breaks down cellulose – a carbohydrate polymer that makes up the walls of plant cells. In fact, cellulose is one of the most abundant organic compounds on Earth. It’s a long chain of glucose units. Once microbes break it down, they gain access to simple sugars, which are a rich, easily digestible source of carbon and energy.

Lignin is a class of complex organic compounds found in the plant cell walls – especially in tougher, more fibrous residues like cereal straw or maize stalks. Like glue, it binds other structural molecules together, giving plants their rigidity and helping them to stand upright. However, this same toughness makes lignin difficult to break down. Certain microbes, especially fungi, produce ligninolytic enzymes to tackle this. These enzymes are chemically powerful tools capable of dismantling these highly resistant structures.

Proteins, on the other hand, are present in all living things – plants, microbes, and animals. When these organisms die, proteins in their tissues are broken down by proteases, enzymes that cut long protein chains into amino acids, which are rich in nitrogen. These amino acids can then be absorbed by microbes, and eventually released back into the soil, where they become valuable nutrients for plant growth.

2. Microbial Assimilation of nutrients

Once the complex molecules have been broken down into smaller compounds, microbes begin to absorb these fragments, taking in simple sugars, amino acids, and other nutrients as sources of energy, carbon, and building blocks for growth.

At this stage, microbes and plants often compete for the same nutrients, particularly nitrogen. In freshly decomposing material, the microbes usually win the race, rapidly absorbing the nutrients and incorporating them into their own biomass. However, this does not harm the ecosystem. In fact, it plays an important ecological role.

When nutrients are tied up in living microbial cells, they are effectively “stored” in the soil, protected from being washed away by rain or lost to the atmosphere. Later, when these microbes die or get consumed by other soil organisms, the nutrients are released back into the soil. This temporary nutrients immobilisation helps regulate nutrient availability over time, acting as a buffer that sustains soil fertility beyond the initial burst of decomposition.

3. formation of stable soil organic matter (SOM)

As decomposition progresses, not all organic matter is fully broken down. Some of it is transformed and stabilized in the soil, contributing to the gradual build-up of soil organic matter (SOM), a critical reservoir of carbon and nutrients that underpins long-term soil fertility.

For decades, scientists believed that this stable SOM was mostly made up of “humus” formed through a distinct process called humification. But newer research tells a different story. Instead of a single, uniform compound, SOM is now understood to be a diverse mix of organic molecules at various stages of decomposition (Lehman and Kleber, 2015). What makes them stable is not their chemical structure alone, but rather how well they are protected from further microbial attack (Lehman and Kleber, 2015).

Surprisingly, soil microbes continue to contribute to the formation of soil organic matter even after they are gone.

Fungal necromass, the remains of fungi after they die, is rich in carbon-dense and structurally complex cell wall components (Qiao et al., 2025). These materials resist decay and contribute significantly to long-term carbon storage. Fungi also produce long thread-like structures called hyphae, which physically bind soil particles together, enhancing soil aggregation and further protecting organic matter from breakdown (Qiao et al., 2025).

Bacterial necromass, by contrast, tends to be more nitrogen-rich and decomposes more quickly, playing a key role in nutrient release rather than long-term storage (Qiao et al., 2025).

what affects the rate of decomposition

While microbial decomposition is a natural process, its speed and efficiency can vary depending on several factors. Just like baking bread depends on the right ingredients, temperature, and timing, decomposition depends on the quality of the organic matter, the condition of the soil, and the diversity of the microbial community.

The type and quality of organic material

The chemical composition of organic matter varies. Some materials are easier for microbes to digest than others.

- Carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio. Materials with a low C/N ratio, such as young green leaves or legume residues, contain relatively more nitrogen. These decompose quickly. On the other hand, materials with a high C/N ratio, like straw or wood chips, are rich in carbon but low in nitrogen. Microbes may struggle to break them down unless additional nitrogen is available.

- Lignin and other complex organic compounds. These compounds are chemically shielding plant residues from microbial break down. High levels of these substances slow decomposition because microbes must invest more energy and specialized enzymes to break through.

environmental conditions in the soil

Microbial activity is also shaped by the physical and chemical environment of the soil.

- Temperature and moisture. Warmer conditions generally speed up microbial metabolism and enzyme activity. Too much water can lead to oxygen-poor conditions that favour slower, anaerobic decomposition. Too little water, and microbial activity decrease significantly.

- Nitrogen availability. While the carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio of organic residues is often discussed, the actual availability of nitrogen in the soil (from natural sources or fertilizer inputs) can profoundly influence the decomposition process. Microbes require nitrogen to grow and function. When nitrogen is limited, especially during the early stages of residue decomposition, microbial activity can stall or shift, as microbes prioritize mining existing soil organic matter for nitrogen.

- Soil pH. Most decomposers prefer slightly acidic to neutral soils. If pH drifts too far from this range, microbial diversity and enzyme activity can decline, reducing the efficiency of organic matter breakdown.

- Soil structure and compaction. In compacted or crusted soils, oxygen and water may be limited, and microbes may struggle to access organic material.

activity and diversity of microbial community

Diverse communities, with a broad range of species and functions, tend to be more efficient and resilient. Some microbes are specialists that excel at breaking down complex compounds, while others are generalists that quickly process simple substrates. A well-balanced microbial ecosystem ensures that all parts of organic matter, from simple sugars to tough lignin, are decomposed efficiently.

Research has shown that the presence of specific microbial groups, such as Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes, is linked to improved decomposition rates and more active nutrient cycling. Farming practices that support microbial diversity can, therefore, directly enhance decomposition and soil fertility.

how to support microbial decomposition in agricultural soils

There are several practical ways to support and enhance microbial decomposition in agricultural systems. These strategies focus on feeding the microbes, protecting their habitat, and boosting their diversity – all of which contribute to healthier, more productive soils.

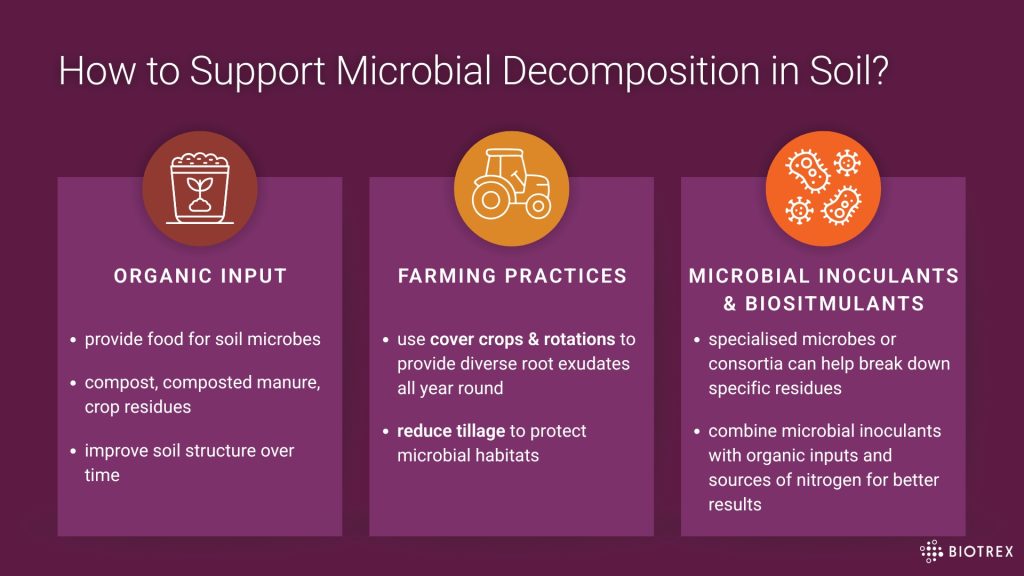

adding organic input

Microbes need food just like any other living organism. In soil, this “food” comes from organic materials such as compost, manure, and crop residues. These inputs not only feed the microbial community but also improve the physical and chemical properties of soil over time.

Long-term use of organic amendments has been shown to increase microbial biomass and enzymatic activity, especially in soils that are low in organic matter. Several studies have demonstrated the practical benefits:

- In semiarid conditions, compost made from sugar beet residues significantly improved microbial activity and increased soil nutrient content, helping plants establish more easily (Mengual et al., 2014).

- When cattle manure is applied alongside chemical fertilizers, soils tend to accumulate more organic matter, support higher microbial populations, and yield better crop performance (Srinivasarao et al., 2014).

- The use of biosolids has been shown to increase the carbon sequestration potential of crop residues compared to soils that receive no organic additions (Tian et al., 2015).

soil management practices that protect soil microbes

Feeding microbes is one part of the equation, but protecting their living environment is equally important. Certain farming practices can create more hospitable conditions for soil life and enhance decomposition.

- Crop rotation introduces a variety of plant species over time, each with different root exudates and residue types. This variety supports a more active and diverse microbial community.

- Reduced tillage or no-till farming minimises soil disturbance (Arcand et al., 2016). Tillage breaks up soil structure and disrupts microbial habitats, while no-till systems help preserve the intricate networks of pores and aggregates that microbes depend on. These undisturbed environments favour higher microbial activity and more stable organic matter.

- Cover cropping keeps the soil biologically active during periods when main crops aren’t growing. Living roots supply a steady stream of carbon through root exudates, while decaying cover crop residues add organic material. This continuous input helps sustain microbial populations and supports year-round decomposition.

using microbial inoculants and biostimulants

In some cases, it’s possible to give decomposition a direct boost by adding beneficial microbes to the soil. These microbial inoculants are often tailored to break down particular types of residue or to function in specific environmental conditions.

- For example, applying a consortium of bacteria and fungi to rice straw, especially when combined with a nitrogen source like urea, can improve the breakdown of tough materials like cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin (Fatima et al., 2025).

- Several fungal species, including Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Coriolus, are well-known for their ability to degrade lignocellulosic compounds (Fatima et al., 2025). Likewise, bacteria such as Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and members of the Actinobacteria group possess powerful enzymatic systems that make them effective decomposers of plant residues (Fatima et al., 2025).

When used alongside organic amendments, microbial inoculants can rebuild degraded soils, speed up nutrient cycling and improve crop performance, particularly in systems where native microbial activity is low or soil conditions are poor.

final thoughts

Microbial decomposition is a foundational process in soil ecosystem, linking the cycling of nutrients and carbon with the maintenance of soil structure and fertility. Its efficiency depends on both environmental conditions and the composition of the microbial community. As agricultural systems face increasing pressure to enhance productivity while mitigating environmental impacts, leveraging the natural capacity of microbial communities to decompose organic matter presents a powerful strategy.

By understanding the factors that influence decomposition, and by adopting practices that support microbial life, we can build soils that are not only more productive but also better equipped to face the challenges of a changing climate and growing global demand for food.

research sources behind this article

Arcand, M. M., Helgason, B. L., & Lemke, R. L. (2016). Microbial crop residue decomposition dynamics in organic and conventionally managed soils. Applied Soil Ecology, 107, 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.07.001

Beier, S., & Bertilsson, S. (2013). Bacterial chitin degradation: Mechanisms and ecophysiological strategies. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00149

Delgado-Baquerizo, M., Trivedi, P., Trivedi, C., Eldridge, D. J., Reich, P. B., Jeffries, T. C., & Singh, B. K. (2017). Microbial richness and composition independently drive soil multifunctionality. Functional Ecology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12924

Fatima, A., Zahid, A., Ali, S., et al. (2025). Microbial consortia-mediated rice residue decomposition for eco-friendly management. Scientific Reports, 15, 32381. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-99613-5

Lehmann, J., & Kleber, M. (2015). The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature, 528, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16069

Mengual, C., Schoebitz, M., Azcón, R., & Roldán, A. (2014). Microbial inoculants and organic amendment improve plant establishment and soil rehabilitation under semiarid conditions. Journal of Environmental Management, 134, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.01.008

Qiao, L., Wang, J., Wei, S., et al. (2025). The soil microbial carbon pump for carbon sequestration. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 23, 1145–1151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-025-01861-4

Srinivasarao, C., Venkateswarlu, B., Lal, R., Singh, A. K., Kundu, S., Vittal, K. P., Patel, J. J., & Patel, M. M. (2014). Long‐term manuring and fertilizer effects on depletion of soil organic carbon stocks under pearl millet‐cluster bean‐castor rotation in western India. Land Degradation & Development, 25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.1158

Tian, G., Chiu, C.-Y., Franzluebbers, A. J., Oladeji, O. O., Granato, T. C., & Cox, A. E. (2015). Biosolids amendment dramatically increases sequestration of crop residue-carbon in agricultural soils in western Illinois. Applied Soil Ecology, 85, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2014.09.001

Zhan, C. Y. (2024). Microbial decomposition and soil health: Mechanisms and ecological implications. Molecular Soil Biology, 15(2), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.5376/msb.2024.15.0007

Zhang, M., Zhang, L., Li, J., et al. (2025). Nitrogen-shaped microbiotas with nutrient competition accelerate early-stage residue decomposition in agricultural soils. Nature Communications, 16, 5793. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-60948-2

Ready to explore how BIOTREX can support your goals?

Book a free call with our experts and discover the impact microbial data can have on your business.